Imagine, someone taking a pencil and drawing a line between the A in Alabama and the L in Los Angeles and making that line the northern frontier of America on a map. Then extending this line down to the M in Mexico City and then back up to the last A in Alabama and making this the United States. Canada would come down to this line. ...and...the person doing this also designed the flag for each country.

The hillbilly culture of Alabama, Texas combined into one state with the Southern California population. Would this cause problems?

Southern states STILL have not given up on their claims to a legitimate hold on the Confederacy. They STILL want to fly their flag despite being defeated by the British in the British Civil War and and again by the Yanks in the American Civil War.

Do you think they would give up when a foreign power carved up their land and combined it with totally different tribes and GAVE them another flag to substitute their confederate AND U.S. Flags...do you think that people would take that well...?

Of course not.

So, with all the fervor over France being bombed by terrorists, in a HORRENDOUS ACT...I must also ask you to look at the reasons why.

How many people putting a French flag on thier profiles have heard of the Sykes-Picot Agreement?

I had not know about this until two years ago and I am an avid student of history.

A French and British diplomat took colored pencils and divided up the middle east for their imperial powers and even designed the flags for Middle Eastern countries during World War I.

No respect for soverienty.

No respect for ancient boundaries.

No respect for tribal laws.

No respect for the people there or their wishes.

No respect for families.

No respect for children.

No respect for their leaders, laws or religions.

The people of The Middle East have been suffering under this miscarrage of justice for more than one hundred years.

They are striking back in the only ways that they can against ruthless superpowers.

Now, I am not advocating violence against Americans, Europeans or any one in the west.

I am not on the side of fanatics that want to distribute indiscriminate violence against innocent people.

I do want to look at both sides of this and to encourage love, compassion and an effort to seek justice.

I want to present the side of the people of The Middle East and their plight instead of the one sided, mass, lame stream media view.

Middle Eastern people are being lynched in France now and in other parts of the western world.

Black people should be particularly sensitive to this.

During a trip to film a documentary in North Dakota about five years ago, I learned that German citizens in the United States were arrested when neighbors reported them playing German music too loud. They were arrested and put into the Snow Prison at Fort Lincoln. This was a SERIOUS thing. They were still on parole as long as 1957. Many of the one's I interviewed had fought against the Nazis in Germany and escaped to American ...only to be put into prison for playing German music! The same happened to the Japanese who were also held at Fort Lincoln (the fort that Custer was based at when he participate in the genocide of native Americans)....and Crystal City, Texas (the same place the many Latinos are being held today when they are FLEEING drug lords (put into place by U.S. drug laws)...who want to put them into prostitution, kill them and or enslave them and their kids.

Please stop, take a look and realize that we have all be indoctrinated, not educated.

Putting that flag on your profile suggests that you are part of the imperial outlook (I know that most of you are not..you just want to support the fine people of France...I do too)....I realize that France helped us defeat the British in the Revolutionary War, they allowed Black people to fly in their air force during WWI. They treated people of color with better freedom and dignity that this country did and does.

That does not assuage the things that were done wrong by the west....the people of The Middle East certainly cannot escape the damage. The face it everyday and continue to be tortured by actions promoted by greed and ignorance.

Please contemplate this post. Please share it. Absorb the information. A Smithsonian article is included along with a Wikipedia story....documenting the crimes of the west..specifically the French and the British.

The Origins of the Sykes-Picot Agreement | History | Smithsonian

The Origins of the World War I Agreement That Carved Up the Middle East

How Great Britain and France secretly negotiated the Sykes-Picot Agreement

By

SMITHSONIAN.COM

image: http://cdn.thinglink.me/api/image/720326630379094017/1024/10/scaletowidth#tl-720326630379094017;1043138249'

Even before the final outcome of the Great War has been determined, Great Britain, France, and Russia secretly discussed how they would carve up the Middle East into "spheres of influence" once World War I had ended. The Ottoman Empire had been in decline for centuries prior to the war, so the Allied Powers already had given some thought to how they would divide up the considerable spoils in the likely event they defeated the Turks. Britain and France already had some significant interests in the region between the Mediterranean Sea and Persian Gulf, but a victory offered a great deal more. Russia as well hungered for a piece.

From November 1915 to March 1916, representatives of Britain and France negotiated an agreement, with Russia offering its assent. The secret treaty, known as the Sykes–Picot Agreement, was named after its lead negotiators, the aristocrats Sir Mark Sykes of England and François Georges-Picot of France. Its terms were set out in a letter from British foreign secretary Sir Edward Grey to Paul Cambon, France's ambassador to Great Britain, on May 16, 1916.

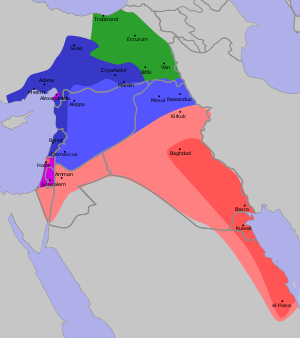

The color-coded partition map and text provided that Britain ("B") would receive control over the red area, known today as Jordan, southern Iraq and Haifa in Israel; France ("A") would obtain the blue area, which covers modern-day Syria, Lebanon, northern Iraq, Mosul and southeastern Turkey, including Kurdistan; and the brown area of Palestine, excluding Haifa and Acre, would become subject to international administration, "the form of which is to be decided upon after consultation with Russia, and subsequently in consultation with the other allies, and the representatives of [Sayyid Hussein bin Ali, sharif of Mecca]." Besides carving the region into British and French "spheres of influence," the arrangement specified various commercial relations and other understandings between them for the Arab lands.

Russia's change of status, brought on by the revolution and the nation's withdrawal from the war, removed it from inclusion. But when marauding Bolsheviks uncovered documents about the plans in government archives in 1917, the contents of the secret treaty were publicly revealed. The exposé embarrassed the British, since it contradicted their existing claims through T. E. Lawrence that Arabs would receive sovereignty over Arab lands in exchange for supporting the Allies in the war. Indeed, the treaty set aside the establishment of an independent Arab state or confederation of Arab states, contrary to what had previously been promised, giving France and Britain the rights to set boundaries within their spheres of influence, "as they may think fit."

After the war ended as planned, the terms were affirmed by the San Remo Conference of 1920 and ratified by the League of Nations in 1922. Although Sykes-Picot was intended to draw new borders according to sectarian lines, its simple straight lines also failed to take into account the actual tribal and ethnic configurations in a deeply divided region. Sykes-Picot has affected Arab-Western relations to this day.

This article is excerpted from Scott Christianson's "100 Documents That Changed The World," available November 10.

Read more: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/sykes-picot-agreement-180957217/#f3BXtErbQR3QJEpW.99

Give the gift of Smithsonian magazine for only $12! http://bit.ly/1cGUiGv

Follow us: @SmithsonianMag on Twitter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sykes%E2%80%93Picot_Agreement

Sykes–Picot Agreement

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Sykes–Picot Agreement | |

|---|---|

Sykes Picot Agreement Map. It was an enclosure in Paul Cambon's letter to Sir Edward Grey, 9 May 1916.

| |

| Created | May 1916 |

| Author(s) | Mark Sykes and François Georges-Picot |

| Signatories | Edward Grey and Paul Cambon |

| Purpose | Defining proposed spheres of influence and control in theMiddle East should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating theOttoman Empire |

The Sykes–Picot Agreement, officially known as the Asia Minor Agreement, was a secret agreement between the governments of the United Kingdom and France,[1]with the assent of Russia, defining their proposed spheres of influence and control in the Middle East should the Triple Entente succeed in defeating the Ottoman Empireduring World War I. The negotiation of the treaty occurred between November 1915 and March 1916.[2] The agreement was concluded on 16 May 1916.[3]

The agreement effectively divided the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire outside the Arabian peninsula into areas of future British and French control or influence.[4]An "international administration" was proposed for Palestine.[5] The terms were negotiated by the French diplomat François Georges-Picot and Briton Sir Mark Sykes. The Russian Tsarist government was a minor party to the Sykes–Picot agreement, and when, following the Russian Revolution of October 1917, the Bolsheviks exposed the agreement, "the British were embarrassed, the Arabs dismayed and the Turks delighted."[6]

Contents

[hide]Territorial allocations[edit]

Britain was allocated control of areas roughly comprising the coastal strip between the sea and River Jordan, Jordan, southern Iraq, and a small area including the ports of Haifa and Acre, to allow access to the Mediterranean.[7] France was allocated control of south-eastern Turkey, northern Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.[7] Russia was to getIstanbul, the Turkish Straits and the Ottoman Armenian vilayets.[7] The controlling powers were left free to decide on state boundaries within these areas.[7] Further negotiation was expected to determine international administration pending consultations with Russia and other powers, including the Sharif of Mecca.[7]

British–Zionist discussions during the negotiations[edit]

Following the outbreak of World War I, Zionism was first discussed at a British Cabinet level on 9 November 1914, four days after Britain's declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire. At a Cabinet meeting David Lloyd George, Chancellor of the Exchequer, "referred to the ultimate destiny of Palestine."[8][9] Lloyd George's law firm Lloyd George, Roberts and Co had been engaged a decade before by the Zionists to work on the Uganda Scheme.[10] In a discussion after the meeting with fellow Zionist Herbert Samuel, who had a seat in the Cabinet as President of the Local Government Board, Lloyd George assured him that "he was very keen to see a Jewish state established in Palestine."[8][11] Samuel then outlined the Zionist position more fully in a conversation with Foreign Secretary Edward Grey. He spoke of Zionist aspirations for the establishment in Palestine of a Jewish state, and of the importance of its geographical position to the British Empire. Samuel's memoirs state: "I mentioned that two things would be essential—that the state should be neutralized, since it could not be large enough to defend itself, and that the free access of Christian pilgrims should be guaranteed. ... I also said it would be a great advantage if the remainder of Syria were annexed by France, as it would be far better for the state to have a European power as neighbour than the Turk"[8][12] The same evening, Prime Minister H. H. Asquith announced that the dismemberment of the Turkish Empire had become a war aim in a speech for the Lord Mayor's Banquet at the Mansion House, "It is the Ottoman Government, and not we who have rung the death knell of Ottoman dominion not only in Europe but in Asia."[13]

In January 1915, Samuel submitted a Zionist memorandum entitled The Future of Palestine to the Cabinet after discussions with Weizmann and Lloyd George. On 5 February 1915, Samuel had another discussion with Grey: "When I asked him what his solution was he said it might be possible to neutralize the country under international guarantee ... and to vest the government of the country in some kind of Council to be established by the Jews"[14][15] After further conversations with Lloyd George and Grey, Samuel circulated a revised text to the Cabinet in mid-March 1915.

Zionism or the Jewish question were not considered by the report of the De Bunsen Committee, prepared to determine British wartime policy toward the Ottoman Empire, submitted in June 1915.[11]

Prior to Sykes's departure to meet Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov in Petrograd on 27 February 1916, Sykes was approached with a plan by Samuel. The plan Samuel put forward was in the form of a memorandum which Sykes thought prudent to commit to memory and then destroy.[citation needed] Commenting on it, Sykes wrote to Samuel suggesting that if Belgium should assume the administration of Palestine it might be more acceptable to France as an alternative to the international administration which she wanted and the Zionists did not. Of the boundaries marked on a map attached to the memorandum he wrote:[8]

Conflicting promises[edit]

Lord Curzon said the Great Powers were still committed to the Reglement Organique Agreement regarding the Lebanon Vilayet of June 1861 and September 1864, and that the rights granted to France in the blue area under the Sykes–Picot Agreement were not compatible with that agreement.[17] The Reglement Organique was an international agreement regarding governance and non-intervention in the affairs of the Maronite, Orthodox Christian, Druze, and Muslim communities.

In May 1917, W. Ormsby-Gore wrote

Many sources report that this agreement conflicted with the Hussein–McMahon Correspondence of 1915–1916. It has also been reported that the publication of the Sykes–Picot Agreement caused the resignation of Sir Henry McMahon.[19] However the Sykes–Picot plan itself described how France and Great Britain were prepared to recognize and protect an independent Arab State, or Confederation of Arab States, under the suzerainty of an Arab chief within the zones marked A. and B. on the map.[20] Nothing in the plan precluded rule through an Arab suzerainty in the remaining areas. The conflicts were a consequence of the private, post-war, Anglo-French Settlement of 1–4 December 1918. It was negotiated between British Prime Minister Lloyd George and French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau and rendered many of the guarantees in the Hussein–McMahon agreement invalid. That settlement was not part of the Sykes–Picot Agreement.[21] Sykes was not affiliated with the Cairo office that had been corresponding with Sherif Hussein bin Ali, but Picot and Sykes visited the Hejaz in 1917 to discuss the agreement with Hussein.[22] That same year he and a representative of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs delivered a public address to the Central Syrian Congress in Paris on the non-Turkish elements of the Ottoman Empire, including liberated Jerusalem. He stated that the accomplished fact of the independence of the Hejaz rendered it almost impossible that an effective and real autonomy should be refused to Syria.[23]

The greatest source of conflict was the Balfour Declaration, 1917 Lord Balfour wrote a memorandum from the Paris Peace Conference in which he asserted Britain's rights suggested that other allies had implicitly rejected the Sykes–Picot agreement by adopting the system of mandates. It allowed for no annexations, trade preferences, or other advantages. He also stated that the Allies were committed to Zionism and had no intention of honoring their promises to the Arabs.[24]

Eighty-five years later, in a 2002 interview with The New Statesman, British Foreign Secretary Jack Straw observed "A lot of the problems we are having to deal with now, I have to deal with now, are a consequence of our colonial past. ... The Balfour Declaration and the contradictory assurances which were being given to Palestinians in private at the same time as they were being given to the Israelis—again, an interesting history for us but not an entirely honourable one."[25]

Events after public disclosure of the plan[edit]

Russian claims in the Ottoman Empire were denied following the Bolshevik Revolution and the Bolsheviks released a copy of the Sykes–Picot Agreement (as well as other treaties). They revealed full texts in Izvestiaand Pravda on 23 November 1917; subsequently, the Manchester Guardian printed the texts on November 26, 1917.[26] This caused great embarrassment between the allies and growing distrust between them and the Arabs. The Zionists were similarly upset,[citation needed] with the Sykes–Picot Agreement becoming public only three weeks after the Balfour Declaration.

The Anglo-French Declaration of November 1918 pledged that Great Britain and France would "assist in the establishment of indigenous Governments and administrations in Syria and Mesopotamia by "setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations". The French had reluctantly agreed to issue the declaration at the insistence of the British. Minutes of a British War Cabinet meeting reveal that the British had cited the laws of conquest and military occupation to avoid sharing the administration with the French under a civilian regime. The British stressed that the terms of the Anglo-French declaration had superseded the Sykes–Picot Agreement in order to justify fresh negotiations over the allocation of the territories of Syria, Mesopotamia, and Palestine.[27]

On 30 September 1918, supporters of the Arab Revolt in Damascus declared a government loyal to the Sharif of Mecca. He had been declared 'King of the Arabs' by a handful of religious leaders and other notables in Mecca.[28] On 6 January 1920 Faisal initialed an agreement with Clemenceau which acknowledged 'the right of Syrians to unite to govern themselves as an independent nation'.[29] A Pan-Syrian Congress meeting in Damascus had declared an independent state of Syria on the 8th of March 1920. The new state included portions of Syria, Palestine, and northern Mesopotamia. King Faisal was declared the head of State. At the same time Prince Zeid, Faisal's brother, was declared Regent of Mesopotamia.

The San Remo conference was hastily convened. Great Britain and France and Belgium all agreed to recognize the provisional independence of Syria and Mesopotamia, while claiming mandates for their administration. Palestine was composed of the Ottoman administrative districts of southern Syria. Under customary international law, premature recognition of its independence would be a gross affront to the government of the newly declared parent state. It could have been construed as a belligerent act of intervention due to the lack of any League of Nations sanction for the mandates.[30] In any event, its provisional independence was not mentioned, although it continued to be designated as a Class A Mandate.

France had decided to govern Syria directly, and took action to enforce the French Mandate of Syria before the terms had been accepted by the Council of the League of Nations. The French issued an ultimatum and intervened militarily at the Battle of Maysalun in June 1920. They deposed the indigenous Arab government, and removed King Faisal from Damascus in August 1920. Great Britain also appointed a High Commissioner and established their own mandatory regime in Palestine, without first obtaining approval from the Council of the League of Nations, or obtaining the formal cession of the territory from the former sovereign, Turkey.

Attempts to explain the conduct of the Allies were made at the San Remo conference and in the Churchill White Paper of 1922. The White Paper stated the British position that Palestine was part of the excluded areas of "Syria lying to the west of the District of Damascus".

Release of classified records[edit]

Lord Grey had been the Foreign Secretary during the McMahon–Hussein negotiations. Speaking in the House of Lords on 27 March 1923, he made it clear that, for his part, he entertained serious doubts as to the validity of the British Government's (Churchill's) interpretation of the pledges which he, as Foreign Secretary, had caused to be given to the Sharif Hussein in 1915. He called for all of the secret engagements regarding Palestine to be made public.[31]

Many of the relevant documents in the National Archives were later declassified and published. Among them were various assurances of Arab independence provided by Secretary of War, Lord Kitchener, the Viceroy of India, and others in the War Cabinet. The minutes of a Cabinet Eastern Committee meeting, chaired by Lord Curzon, held on 5 December 1918 to discuss the various Palestine undertakings makes it clear that Palestine had not been excluded from the agreement with Hussein. General Jan Smuts, Lord Balfour, Lord Robert Cecil, General Sir Henry Wilson, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and representatives of the Foreign Office, the India Office, the Admiralty, the War Office, and the Treasury were present. T. E. Lawrence also attended. According to the minutes Lord Curzon explained:

On 17 April 1964, The Times of London published excerpts from a secret memorandum that had been prepared by the Political Intelligence Department of the British Foreign Office for the British delegation to the Paris peace conference. The reference to Palestine said:

Another document, which was a draft statement for submission to the peace conference, but never submitted, noted:

Lloyd George's explanation[edit]

The British Notes taken during a 'Council of Four Conference Held in the Prime Minister's Flat at 23 Rue Nitot, Paris, on Thursday, March 20, 1919, at 3 p.m.'[36]shed further light on the matter. Lord Balfour was in attendance, when Lloyd George explained the history behind the agreements. The notes revealed that:

- '[T]he blue area in which France was "allowed to establish such direct or indirect administration or control as they may desire and as they may think fit to arrange with the Arab State or Confederation of Arab States" did not include Damascus, Homs, Hama, or Aleppo. In area A. France was "prepared to recognise and uphold an independent Arab State or Confederation of Arab States'.[37]

- Since the Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916, the whole mandatory system had been adopted. If a mandate were granted by the League of Nations over these territories, all that France asked was that France should have that part put aside for her.

- Lloyd George said that he could not do that. The League of Nations could not be used for putting aside our bargain with King Hussein. He asked if M. Pichonintended to occupy Damascus with French troops. If he did, it would clearly be a violation of the Treaty with the Arabs. M. Pichon said that France had no convention with King Hussein. Lloyd George said that the whole of the agreement of 1916 (Sykes–Picot), was based on a letter from Sir Henry McMahon' to King Hussein.[38]

- Lloyd George, continuing, said that it was on the basis of the above quoted letter that King Hussein had put all his resources into the field which had helped us most materially to win the victory. France had for practical purposes accepted our undertaking to King Hussein in signing the 1916 agreement. This had not been M. Pichon, but his predecessors. He was bound to say that if the British Government now agreed that Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo should be included in the sphere of direct French influence, they would be breaking faith with the Arabs, and they could not face this.

Lloyd George was particularly anxious for M. Clemenceau to follow this. The agreement of 1916 had been signed subsequent to the letter to King Hussein. In the following extract from the agreement of 1916 France recognised Arab independence: "It is accordingly understood between the French and British Governments.-(1) That France and Great Britain are prepared to recognise and uphold an independent Arab State or Confederation of Arab States in the areas A. and B. marked on the annexed map under the suzerainty of an Arab Chief." Hence France, by this act, practically recognised our agreement with King Hussein by excluding Damascus, Homs, Hama, and Aleppo from the blue zone of direct administration, for the map attached to the agreement showed that Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo were included, not in the zone of direct administration, but in the independent Arab State. M. Pichon said that this had never been contested, but how could France be bound by an agreement the very existence of which was unknown to her at the time when the 1916 agreement was signed? In the 1916 agreement France had not in any way recognised the Hejaz. She had undertaken to uphold "an independent Arab State or Confederation of Arab States", but not the Kingdom of Hejaz. If France was promised a mandate for Syria, she would undertake to do nothing except in agreement with the Arab State or Confederation of States. This is the role which France demanded in Syria. If Great Britain would only promise her good offices, he believed that France could reach an understanding with Feisal.'[39]

Consequences of the agreement[edit]

The agreement is seen by many as a turning point in Western–Arab relations. It negated the promises made to Arabs[40] through Colonel T. E. Lawrence for a national Arab homeland in the area of Greater Syria, in exchange for their siding with British forces against the Ottoman Empire.

The agreement's principal terms were reaffirmed by the inter-Allied San Remo Conference of 19–26 April 1920 and the ratification of the resulting League of Nations mandates by the Council of the League of Nations on 24 July 1922.

The Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) claims one of the goals of its insurgency is to reverse the effects of the Sykes–Picot Agreement.[41][42][43] "This is not the first border we will break, we will break other borders," a jihadist from the ISIL warned in the video called End of Sykes-Picot.[44] ISIL's leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in a July 2014 speech at the Great Mosque of al-Nuri in Mosul vowed that "this blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes–Picot conspiracy".[45][46]

The Franco-German geographer Christophe Neff wrote that the geopolitical architecture founded by the Sykes–Picot Agreement has disappeared in July 2014 and with it the relative protection of religious and ethnic minorities in the Middle East.[47] He claims furthermore that Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant has in some way restructured the geopolitical structure of the Middle East in summer 2014, particularly in Syria and Iraq.[48] The former French Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin has presented a similar geopolitical analysis in an editorial contribution for the French newspaper Le Monde.[49]

See also[edit]

- Syrian Social Nationalist Party

- Covenant Society

- Geography of Syria

- Geography of Saudi Arabia

- Unification of Saudi Arabia

- French colonial flags

- French Colonial Empire

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Calouste Gulbenkian

- Alawite State

References[edit]

- ^ Fromkin, David (1989). A Peace to End All Peace: The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East. New York: Owl. pp. 286, 288. ISBN 0-8050-6884-8.

- ^ The Middle East in the twentieth century, Martin Sicker

- ^ http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/collection/LimitsinSeas/IBS094.pdfp. 8.

- ^ Peter Mansfield, British Empire magazine, Time-Life Books, no 75, p. 2078

- ^ Eugene Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans, p.286

- ^ Peter Mansfield, The British Empire magazine, no. 75, Time-Life Books, 1973

- ^ a b c d e Text of the Sykes–Picot Agreement at the WWI Document Archive

- ^ a b c d Grooves Of Change: A Book Of Memoirs, Herbert Samuel

- ^ Britain's Moment in the Middle East, 1914-1956, Elizabeth Monroe, p26

- ^ Conservative Party attitudes to Jews, 1900–1950, Harry Defries

- ^ a b A Broken Trust: Sir Herbert Samuel, Zionism and the Palestinians, Sarah Huneidi, p261 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Huneidi" defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Samuel, Grooves of Change, p174

- ^ J Schneers, "Balfour Declaration" (London 2012)[this quote needs a citation]

- ^ Samuel, Grooves of Change, p176

- ^ In the Anglo-Arab Labyrinth, Elie Kedourie

- ^ The high walls of Jerusalem: a history of the Balfour Declaration and the birth of the British mandate for Palestine, 1984, p346

- ^ CAB 27/24, E.C. 41 War Cabinet Eastern Committee Minutes, December 5, 1918

- ^ See UK National Archives CAB/24/143, Eastern Report, No. XVIII, May 31, 1917

- ^ See CAB 24/271, Cabinet Paper 203(37)

- ^ see paragraph 1 of The Sykes–Picot Agreement

- ^ Allenby and British Strategy in the Middle East, 1917–1919, Matthew Hughes, Taylor & Francis, 1999, ISBN 0-7146-4473-0, pages 122–124

- ^ Isaiah Friedman, Palestine, a Twice-promised Land?: The British, the Arabs & Zionism, 1915–1920 (Transaction Publishers 2000), ISBN 1-56000-391-X, p.166

- ^ Foreign Relations of the United States, 1918. Supplement 1, The World War Volume I, Part I: The continuation and conclusion of the war—participation of the United States, p.243

- ^ Document 242, Memorandum by Mr.Balfour (Paris) respecting Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia, 11 August 1919, in E.L.Woodward and Rohan Butler, Documents on British Foreign Policy, 1919–1939. (London: HM Stationery Office, 1952), ISBN 0-11-591554-0, p.340–348, [1]

- ^ New Statesman Interview – Jack Straw

- ^ http://www.law.fsu.edu/library/collection/LimitsinSeas/IBS094.pdfp. 9.

- ^ See Allenby and General Strategy in the Middle East, 1917–1919, By Matthew Hughes, Taylor & Francis, 1999, ISBN 0-7146-4473-0, 113-118

- ^ Jordan: Living in the Crossfire, Alan George, Zed Books, 2005, ISBN 1-84277-471-9, page 6

- ^ Britain, the Hashemites and Arab Rule, 1920–1925, by Timothy J. Paris, Routledge, 2003, ISBN 0-7146-5451-5, page 69

- ^ see for example International Law, Papers of Hersch Lauterpacht, edited by Elihu Lauterpacht, CUP Archive, 1970, ISBN 0-521-21207-3, page 116 and Statehood and the Law of Self-determination, D. Raič, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2002, ISBN 90-411-1890-X, page 95

- ^ Report of a Committee Set Up To Consider Certain Correspondence Between Sir Henry McMahon and The Sharif of Mecca

- ^ cited in "Palestine Papers, 1917–1922", Doreen Ingrams, page 48 from the UK Archive files PRO CAB 27/24.

- ^ "Light on Britain's Palestine Promise". The Times. April 17, 1964. pp. 15–16.

- ^ Elie Kedourie (April 23, 1964). "Promises on Palestine (letter)". The Times. p. 13.

- ^ A Line in the Sand, James Barr, p.12

- ^ 'The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919, page 1'

- ^ 'The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919, page 6'

- ^ The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919, Page 7

- ^ The Council of Four: minutes of meetings March 20 to May 24, 1919, Page 8

- ^ Hawes, Director James (21 October 2003). Lawrence of Arabia: The Battle for the Arab World. PBS Home Video. Interview with Kamal Abu Jaber, former Foreign Minister of Jordan.

- ^ "This is not the first border we will break, we will break other borders," a jihadist from ...]". www.theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ "Watch this English-speaking ISIS fighter explain how a 98-year-old colonial map created today’s conflict". LA Daily News. 7 February 2014. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ Phillips, David L. "Extremists in Iraq need a history lesson". CNBC.

- ^ Tran, Mark and Weaver, Matthew (30 June 2014). "Isis announces Islamic caliphate in area straddling Iraq and Syria". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ^ "Exclusive: First Appearance of ISIS Caliph in Iraq Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi (English Subtitles)". LiveLeak.com. 5 July 2014. Retrieved11 August 2014.

- ^ Zen, Eretz. "Is Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi the Man in the Recent ISIL Video?". YouTube.com.

We have now trespassed the borders that were drawn by the malicious hands in lands of Islam in order to limit our movements and confine us inside them. And we are working, Allah permitting, to eliminate them (borders). And this blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy.(transl.)

- ^ "Bientôt le souvenir de l’église catholique chaldéenne et des églises syriaques (orthodoxes & catholiques) sera plus qu’un souffle de vent chaud dans le désert (In French)". paysages in LeMonde.fr. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ "Yazidis d’Irak – le cri d’angoisse d’une députée du parlement irakien (In French)". paysages in LeMonde.fr. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

- ^ "" Ne laissons pas le Moyen-Orient à la barbarie ! " par Dominique de Villepin (In French)". LeMonde.fr. Retrieved August 10, 2014.

No comments:

Post a Comment